今日(21日)は久しぶりによい天気(秋晴れ)。忙しい一日であった。

⓵ 久しぶりの天気で、たくさんの洗濯物と布団を2階のベランダに干す。

② 家の前の小学校でやっている「緑オリンピック」(青少年育成委員会主催)に親と子ども(孫)が行くのに同行する。子どもは小学生の合唱や中学生の吹奏楽、紙工作を楽しんでいた。地域の知り合いの高齢者が、子ども達にいろいろ昔の遊びを教えていた。

③ 自転車で5分のところにある公共の体育館に行き、卓球愛好会の練習に1時間ほど参加する。数分交代で、次々相手が変わる。卓球を学生の頃からやっているあるいは週に4回以上卓球をやるという人が多く、球のスピードは速く、それについて行くのがやっと。1時間で退出。

④ 家のそばのバス停を1時間に2本通るバスに10分乗り、降りたバス停から10分歩いて敬愛大学に行き、大学祭(敬愛フェスティバル)を見学する。

敬愛フェスティバルは、見学したのが最終日の午後だったせいもあり、もう祭りのおわりの哀愁も漂っていた。でも、学生それぞれが楽しんでいる様子で、小さな大学の大学祭のよさを感じた。

顔見知りの学生に声をかけられ、模擬店の食べ物をいくつか購入し、学内の催しものを見て回った。地域の子ども向けのものもあった。私の授業を受講したことがある女子学生二人のさわやかなギターの弾き語りを聴き、1年の時のゼミ生の豊田君がボーカルの軽音の男4人のロックバンドがとても上手で、聞き惚れた。「この4年間の大学生活にはいいこともあったけれど、不満もたくさんあり、その気持ちを思いっきりぶつけます」という語りがあり、熱の入った演奏で、大学生の心情に心打たれた。

⑤研究室で訪ねてきた上智の卒業生から今の入学試験に関する情報を聞く。東京の私立中学の英語のレベルルが英検2級程度のところがある、数学の問題を英語で出すところがあると聞き、東京の私学のお受験のレベルの高さに驚く。東京の予備校に通う高校生の英語の答案を見て、そのレベルの高さに驚く(自由英作文で、英語で自分の意見をすらすら書いている)。

とても忙しい秋の充実した1日であった。締めくくりにこのブログを書く。

カテゴリー: 未分類

大学人と所属について

私たち研究者も所属がいろいろなところで関係する。学会で発表する時のプログラムには、名前の前に所属(○○大学等)が掲載されている。学会の発表の時質問する時も、「名前と所属を言って下さい」と司会者から言われる。

全く個人資格で研究し発表しているのに、なぜ所属を表示する必要があるのだろうと思う。

銘柄大学の所属や肩書がついていると、何か偉そうに見え、威光効果があるのかもしれない。

何かのシンポジウムやパネルディスカッションでも、登壇者の所属が大事で、名の知れた大学の教員が選ばれることが多い。また大学人の移動をみると、偏差値の高い大学や有名な大学へという流れがある。

ただ本当に優秀な人は、所属に関係なく、その人の名前が知れ渡っていて、名前が一流の証明になっている。本人も所属大学は気にせず、自分の研究条件に有利になれば、銘柄大学からそうでない大学や所属に移る場合がある。でもそれが出来るのは、ごく一部の優秀な、そして勇気ある研究者である。

私たちの世代やその前の世代は、そのような勇気ある研究者・大学人はあまりいなかったように思うが、後続世代にそのような優秀な勇気ある研究者が出始めている。

教育社会学では、苅谷剛彦氏や広田照幸氏が東大教授の身分を蹴って他に移っているし、最近ではアクティブラーニングの研究でも有名な溝上慎一氏が京大教授を辞して桐蔭学園に移っている(smizok.net)。

肩書ではない実力で勝負する若い大学研究者に、我々古い世代も鼓舞されることが多い。

秋の朝顔

暑さが去ったと思ったら、急に寒くなり、紅葉の季節を迎えている。

この異常気象で、草木も戸惑っていることであろう。

家の庭や近所でも夏の朝顔が、10月中旬の今も、咲いている。

追記 天声人語(10月19日)にも次のような記述がみられる。

<いまあちこちで季節外れの桜が咲いている。(中略)▼秋のさわやかな空気のなかで桜の花が見られるのかなと思い、東京の目黒川沿いを歩いた。よく探すと1輪、2輪と白い花がある。ほとんどの花芽は、春まで待ってくれるのだろう▼季節外れの開花を「狂い咲き」という。植物たちの方がおかしくなったような言い方で、かわいそうでもある。異常続きのこの国の気象に、私たちと同じように、木々も振り回されている。>

教育課程論(第3回)の記録

昨年の授業内容とあまり変わりがないが、少しは資料を追加し、新たな問も出しているので、先週(10月12日)の敬愛大学での授業(教育課程論)の記録を残しておきたい。

授業のテーマは、(新)学習指導要領の趣旨、キーコンセプトについて。

配布資料は⓵前回のリアクションのコピー、②文部科学省「生きる力」、③松尾知明「教育課程論・方法論」第1章、⓸松尾知明『21世紀型スキルとは何か」、⑤武内清・教育社会学研究室ブログである。(添付参照)

前回の授業で、学習指導要領の変遷と2017年3月告示の新学習指導要領の総則部分はプリントして説明したので、そのリアクションを使い復習をした後、上記の資料を配布して、下記のリアクションの問いに答えてもらった。(実際のリアクションも一部添付する)

教育課程論(第3回)リアクション 2018年 10月12日

1 武内ブログへのコメント

2 「生きる力」とは(「これからの時代に求められる力とは」(文部科学省)参照)

3 「確かな学力」とは(同上)

4 2017年(新)学習指導要領改訂の趣旨は何か。無藤隆『学習指導要領改訂のキーワード』参照。

5 アクティブ・ラーニングとは何か (同上)

6 コンピテンシーとは何か(松尾「教育課程・方法論」第1章参照)

7 21世紀型能力とは何か(松尾「21世紀型スキルとは何か」参照)

8 これからの社会で、どのような能力が必要とされていると思うか。(自分の考え)

9 他の人のコメントをもらう。

( )→

学生は、短時間で多くの資料を読んで、要点を理解してくれた。そのことがリアクションの内容からもわかる。

学習指導要領に詳しいU氏にこの授業の資料と学生のリアクションを見てもらったところ、下記の感想をいただいた。

<武内先生の講義資料と学生さんのレポート、拝見しました。正直、驚きました.ここまで本格的に展開されているとは思いませんでしたので。この資料に学生さんたちがついていくのは大変だと思います。しかし、それでも、レポートの内容から、なんとか理解して、一生懸命自分の考えをまとめようとされていることが読み取れます。>

IMG_20181017_0002

IMG_20181014_0002

IMG_20181014_0003

IMG_20181017_0001

読書談義

先週のNHKスペシャルでは、健康年齢を若くするためには、「本や雑誌を読む」(読書)が一番いいという結果を、AI(人工知能)が出しているということが話題になっていた。

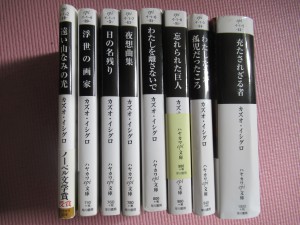

敬愛大学の1年生の授業で、「カズオ・イシグロの本を読んだことのある人」と聞いたら、皆無であった。ノーベル文学賞を獲った人の本ですらこのあり様であるから、大学生の読書離れはかなり進んでいるのであろう。(そうは言う私もこの頃読書量は減っているので、偉そうなことは言えないが)。

仙台にいる水沼さんと、読んだ本のことがメールで、少し話題になった。(一部転載)

(水沼)大学生に先生のブログの記事を読ませて意見を聞くのはアイデアだと思います。大学の教材にはなかなかありませんからね。学者とか学問とかが学生たちに身近に感じさせる機会になると思います。

私は「日の名残り」を読み直し始めました。すばらしい作品は何度読んでもいいもの

です。

(武内)「日の名残り」は、私も一番印象に残っている本で、英語でも読もうと試みましたが、挫折しています。DVDも購入したのですが、どうしたことか、うちの器械でうまく再生できず。そのままになっています。再度、試みるつもりです。

(武内)前回出したメールに誤りがありました。私がカズオ・イシグロの小説で、一番感銘を受けたのは、最初に読んだ「私を離さないで」でした。途中でクローン人間の話と分かりその心情に思いやり、とても衝撃を受けました。

「日の名残り」も伝統的なイギリスらしさがわかり、いい小説だと思いました。ただ主人公の執事の行動がもどかしく、現代の人が読んだら、なかなか共感できないと思いました。 昨日、私も「日の名残り」を読みかえし、アマゾンでレンタルしてテレビで、映画も見ました。やはり、最初に本で読んでしまうと、映画の方は「そこは少し違うな」と思ってしまう箇所がいくつもありますね。ミス・ケントは、小説で想像していたより素敵な女性でしたが。

(水沼)父の代からの執事の仕事に誇りを持ちながら貴族社会では執事は執事に過ぎません。アメリカから新しいご主人がやってきて、主人公を人間らしく扱います。そして主人公はご主人の車で昔の女性パートナーをリクルートに行きます。

階級という社会が作り出した偏見のもと、旅をしながら貴族の振りをする主人公が哀れですね。最終的に彼が何を得たのか分かりません。武内先生がおっしゃる「まどろかっしさ」がそこにあります。

カズオ・イシグロはタイトルですべてを語るところがあります。「日の名残り」に私は蕪村の「山は暮れて野は黄昏の薄かな」を連想します。子どもの頃、遊びに遊んだ一日が終わり、友達が一人ひとり家に帰り、田んぼの真ん中に独り取り残された私が見た光景が「日の名残り」でした。私にとっての「いい時代」が終わり、競争社会に取り込まれていく境目だったのです。

雑草だらけの庭から昔のままの国見峠に沈む夕日を見ることができます。「日の名残り」に魅かれるのはこんなところから来ているのかも知れません。

(「日の名残り」に関しては、2018年2月18日のブログでも言及している)

追記 卒業生より下記のコメントをもらった。

<そもそも人生で読書らしきものをしたことがない学生も多そうですが、現在、または過去にどのような読書をしてきたかを聞いてみると面白いのでは? 斎藤孝が『読書力』かどこかで、そもそも大学生(しかも教職課程)で読書の価値自体を認めない/否定する層がいることを書いています(『読書力』自体が10年以上前の本ですが)。読んでいなくて恥ずかしい、という前提自体が必ずしも成り立たない。>